THE JOURNEY OF ONE MAN

In 1995 Jose Maria Joao went awol. Conscripted as a child-soldier into UNITA, Jose, as he prefers to be called, was caught into an unwinnable Angolan civil war. Jose’s wife and child died in that drawn-out and failed rebellion; burnt inside their home. Jose was fighting in the north at the time, and it was their deaths which proved the tipping point. At that point he’d been fighting non-stop for 5 years.

From the outside – the becalmed luxury of a retrospective conversation while seated in a Cape Town gallery on Church street – it is impossible to truly grasp the immensity of the emotional and psychological pain that comes with such a deep loss, both personal and political. Listening to Jose – now domiciled in South Africa for 15 years – one senses the pain, but also, and all importantly, the belief that life must continue.

While Jose received his residency permit 10 years ago, his work permit is still pending. A survivor – and one cannot use this word lightly – Jose has managed to make a good life for himself in Cape Town. A ‘bouncer’ at The Power & The Glory on Kloof Street – a bar whose name couldn’t prove more poignant – Jose has become a local legend. Revered by the bar’s clientele, Jose has also proved a brilliant ambassador and guide for the city’s unending stream of tourists.

If he is also a highly sought after mountain guide it is because of the strength and goodwill he exudes. That Jose is also mesmerizingly present – given the mix of his massive build with his gentleness – he automatically impresses himself upon the imagination. He is a man of our times – a man of Empathy. With a profound capacity to connect with others and share their dreams, Jose is inspirational. The epitome of ‘ubuntu’.

‘My job is to make peace, make everyone happy,’ says Jose. ‘I don’t want violence anymore’. Given that Jose is a trained soldier, and a boxer to boot, these words are all the more remarkable.

Seated across from me at the Worldart gallery, his powerful frame at odds with the effetely angled vinyl armchair, Jose recounts his own long walk to freedom. ‘Why the killing, why the fighting,’ he begins, then details his gruelling march from Wambo in the north of Angola down through Unjiva, before slipping invisibly across the Namibian border into Ondangwa where, finally, he rid himself of his UNITA fatigues.

Having successfully walked down the length of Angola, Jose slipped into the back of a truck carrying a cargo of braai wood, travelling another 100km to Windhoek. In Namibia he secured ‘refugee status,’ but found himself stranded in a camp with no purpose other than one of numbing lassitude.

After this he was employed as a labourer on a farm for 3 years. Housed and fed, he received no remuneration. Realising the futility of his life Jose escaped the farm, little more than a slave labour camp in the province of Uchiwanrongo, and walked down through Mariental, before crossing the border into South Africa along the Orange River.

Jose was lucky perhaps in meeting a South African truck driver who could see his goodness, for the trip down to Cape Town was effortless. As Jose puts it, the ‘coloured’ truck driver was the ‘listener to a true story.’ Between Jose, the refugee from an Angolan civil war, and the South African truck driver who rescued him, we find this clear and true understanding. Africans both; each understood the other as ‘a piece of the continent, a part of the main’. Every day, Jose tells me, he anticipates encountering this kind man who drove him all the way down to Epping on the industrial outskirts of Cape Town.

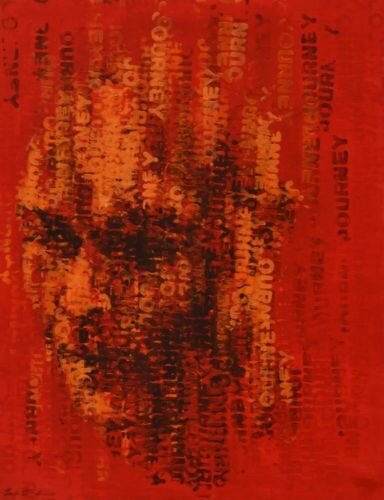

Now resident in Cape Town with a flat in Gardens, Jose is making his own way. A local cult figure, and a beacon of light, it is not surprising that Charl Bezuidenhout, the director of Worldart, should find that he too is crossing paths with Jose Maria Joao. It is their connection which resulted in my own. If I am here to recount Jose’s story it is because something else is afoot: Charl Bezuidenhout has commissioned the Durban-born artist Claude Chandler to do a series of paintings of Jose.

Looking at Chandler’s work I realise that we are not really speaking about portraits, but about paint as a kind of sonar – a strangely legible yet abstract rendering of a being’s affect. True, Jose is as impressive as an Easter Island stone cutting, and yet it is not the power of his physical bearing that compels as much as the man’s energy. It is here that Chandler plays his part in this story, for in his ability to capture energy, momentarily stabilise the unstable, and gift us with character as something active, something molecular, Chandler also promises to rethink what matters; what makes us human.

Jose Maria Joao is the medium, but he is also the real thing – the kind of being and story which, today, we most cherish. Physically impressive, yet infinitely gentle, he is our X-Man, our Homo Empathicus. As Roman Krznaric reminds us, ‘We need to recognise that empathy doesn’t just make you good – it’s good for you’. And I think it is this intuition which connects Charl Bezuidenhout to Jose Maria Joao to Claude Chandler.

Concluding my conversation with Jose, I ask him for his email address. ‘My email is my face’, he says, and in saying this I realise that it is not mere physiognomy which he is referring to but the energy which that face – more than mere stony autograph – communicates.

Written by Ashraf Jamal